Bugles announce spring in Interior Alaska. There are no brass instruments glinting in the late April sun, no uniformed musicians standing in the slumping snow drifts. Instead, the hopeful tune comes from above and is played by one of nature’s finest horners, the Sandhill Crane.

Some people might protest that it’s the honking of Canada Geese that marks the end of winter. It’s a fair argument, since the geese are usually audible a week or so before the cranes.1 But after the decade I spent living on the edge of Creamer’s Field Migratory Waterfowl Refuge in Fairbanks, where thousands upon thousands of both species congregate in spring and fall, I still vote for the Sandhills.

Maybe it’s because spring - ‘break-up’ to Interior Alaskans, a reference to the cracking of the thick ice atop the lakes and rivers - is a fickle season. The weather will be a marvelous 50F for a day or two, then fall back below freezing and drop two or three inches of wet snow. The first half of April is notorious for this kind of bait-and-switch. I suppose I always took the Canada Goose’s cry, which usually begins to ring out around the middle of the month, as nasally laughter at our human despair.

If the Canada Goose is the mean girl teasing us for daring to dream of warmer days, the Sandhill Crane is the wise parental figure whose arrival softens the teasing. Ignore those silly geese, for they’ll soon move on to laugh at others. I’m here now, the snow is going, and soon the trees will bud. All is well.

It’s a believable message. Canada Geese look like they could brave a sub-arctic winter, with their bulky bodies and short, thick legs. Sandhill Cranes don’t. Although they’re typically the heavier of the two species, their tapered figures, long legs, and broad wings (up to a foot wider in span than a Canada Goose’s) don’t scream ‘deep-freeze resilient.’ A comparison of wintering grounds backs this visual conclusion up. While Canada Geese overwinter as far north as Illinois and Colorado, the bulk of the Sandhill Crane population keeps south of the Texas Panhandle.2

Sandhills’ figures trigger thoughts of ballerinas for a good reason. Not only are Sandhill Cranes long-distance travelers, accomplished buglers, and loyal lovers, but they’re dancers, too. Their elaborate communication routines were a late-May delight when I lived alongside Creamer’s Field. The leaps and pirouettes worthy of the Bolshoi enticed me out of bed and into the chilly dawn almost every single day.

The main paths through Creamer’s Field form a tilted L, with the old dairy farm buildings at one end and my neighborhood at the other. At five o’clock, the night’s mist would still be clinging to the soil of the open fields, hiding all but the tallest tufts of grass. Occasionally a low call would penetrate the sound-dampening blanket from ground level, but the call that truly broke the silence always came over the tops of the surrounding boreal forest. Aldo Leopold’s description of the moment when the earliest-rising birds come looking for their worms sums the sight up perfectly:

On motionless wing they emerge from the lifting mists, sweep a final arc of sky, and settle in clangorous descending spirals to their feeding grounds. A new day has begun on the crane marsh.

And so it was, for that first cry spawned a thousand more. I would walk to the old farm and back, and in the quarter hour this took the cranes awakened. On my return trip, I would often have to stop to let groups of them cross my path. More frequently, I stopped of my own accord to watch them dance.

On days when the Sandhills were especially exuberant, my walk might take two or three time longer than it did during crane-free seasons. I returned home cold but smiling, aware that though I’d been the only spectator at that morning’s recital (for I rarely encountered other humans in the field at that hour), variants of the same show had been seen by hundreds of generations before me.

This is not an exaggeration. Sandhill Cranes were living in what is now Florida at least 2.5 million years ago.3 Florida is still part of their range, so there’s good reason to think that they may also have migrated to and bred in the ice-free haven of Interior Alaska during the Pleistocene Glacial Maximum.4 If so, then the Sandhill Cranes and their gravity-defying dancing may have been one of the first signs to Beringian peoples that they were entering a new world.

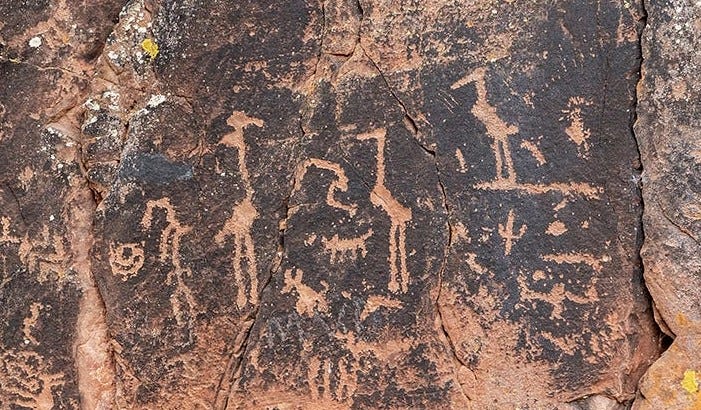

Familiarity with the Sandhills didn’t (and doesn’t) make them boring. The Crane Petroglyph Heritage Site near Sedona, Arizona is evidence of this. It isn’t the work of a moment to carve a symbol deep enough into stone that it lasts for more than 600 years. Here, however, the Southern Sinagua people of the Beaver Creek Community drew many cranes alongside other animals.

Sandhill Cranes still flock to Arizona in large numbers. In 2024, over 42,000 wintered in the southeastern corner of the state.5 These aren’t the same cranes that I greeted the day with in Fairbanks, since Arizona’s cranes spend summers in the Rocky Mountains and along the Colorado River6, but that doesn’t make them any less magical. Though they’re technically different subspecies, Arizona’s cranes look the same, sound the same, and dance the same as Alaska’s do. The only obvious difference to the layperson is that the bugling of Arizona’s cranes foretells the coolness of winter instead of the warmth of spring.

It’s an equally relieving change of weather, but there’s extra cause for excitement when the cranes return to the south. That extra excitement is due not to the cranes themselves, but to a very different Arizona creature; snakes.

Although you can encounter snakes in southern Arizona at any time of year, they typically become less active in October or November7, right around the time that the first Sandhills arrive. From a scientific perspective, these two events are unrelated except for being responses to seasonal changes in temperature. From a mythological standpoint, though, one could make a tongue-in-cheek case for the cranes chasing the snakes away.

Science now knows the Sandhill Crane as Antigone canadensis. Antigone of Troy, for whom the genus was allegedly named, is reputed to have claimed that she was more beautiful than the goddess Hera. Hera’s reply was to turn Antigone’s hair into snakes. Other gods later overrode this extreme punishment with the far less horrifying fate of being turned into a stork. This, the myth suggests, is why storks eat snakes.

Cranes aren’t storks, of course, even if their scientific name suggests it in what seems at first glance to be a misnomer8. But like storks, they do eat snakes.

It would be quite a leap to seriously argue that the telltale calls of the returning Sandhills are what drive Arizona’s snakes underground in late fall. But like many desert dwellers, I tread easier on the trail when the snakes are sluggish, regardless of the reason for their retreat. Maybe I shouldn’t take the sound of Sandhills as a sign of relative safety, especially since there are still Canada Geese laughing overhead around the same time. Still, I crane upward in fall as I once did in spring, and strain my ears for bugles.

(Endnote: in writing this piece, I found myself questioning my capitalization choices with ‘Sandhill Crane’ and ‘Canada Goose.’ In the end I chose to go with title case, partly because it was my natural inclination and partly because of this blog post by Ron Dudley at Feathered Photography.)

The Alaska Songbird Institute has compiled this handy list of dates when each common migratory species arrives in Fairbanks. Microsoft Word - arrival dates.docx

According to the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology, which states that a definite Sandhill Crane fossil from the Macasphalt Shell Pit dates to that age. Sandhill Crane Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Returning cranes set record in return, Arizona Daily Star, 12 January 2024.

Per the Arizona Game and Fish Department; Sandhill crane - Arizona Game & Fish Department.

Per the Arizona Game and Fish Department; Spring months active time for rattlesnakes - Arizona Game & Fish Department

They don’t even share the same Order or Family as storks. And until 2010, Sandhill Cranes were listed with most other cranes under the genus Grus, which is Latin for…crane. It was only after DNA sequencing was done that the scientific world determined that Sandhill Cranes and three other species ought to be in their own genus, and resurrected the Antigone name (which had been used in scientific naming in the 19th century, but had since gone dormant) for them.