Sometimes I think I have written many of my poems against my will. I think this must be true for a great number of poets. A poet, like any artist, is sensitive; being sensitive means living as an exposed nerve. As such, poets are nervous all the way through — from the first inkling of inspiration to the completed poem on the page.

But the poem the reader sees — that is to say, not the poem as the poet conceives it — is not the poem in and of itself. It is, in essence, a kind of distillation of the poem. For the poem has undergone an alchemical process of changing it from one thing into another.

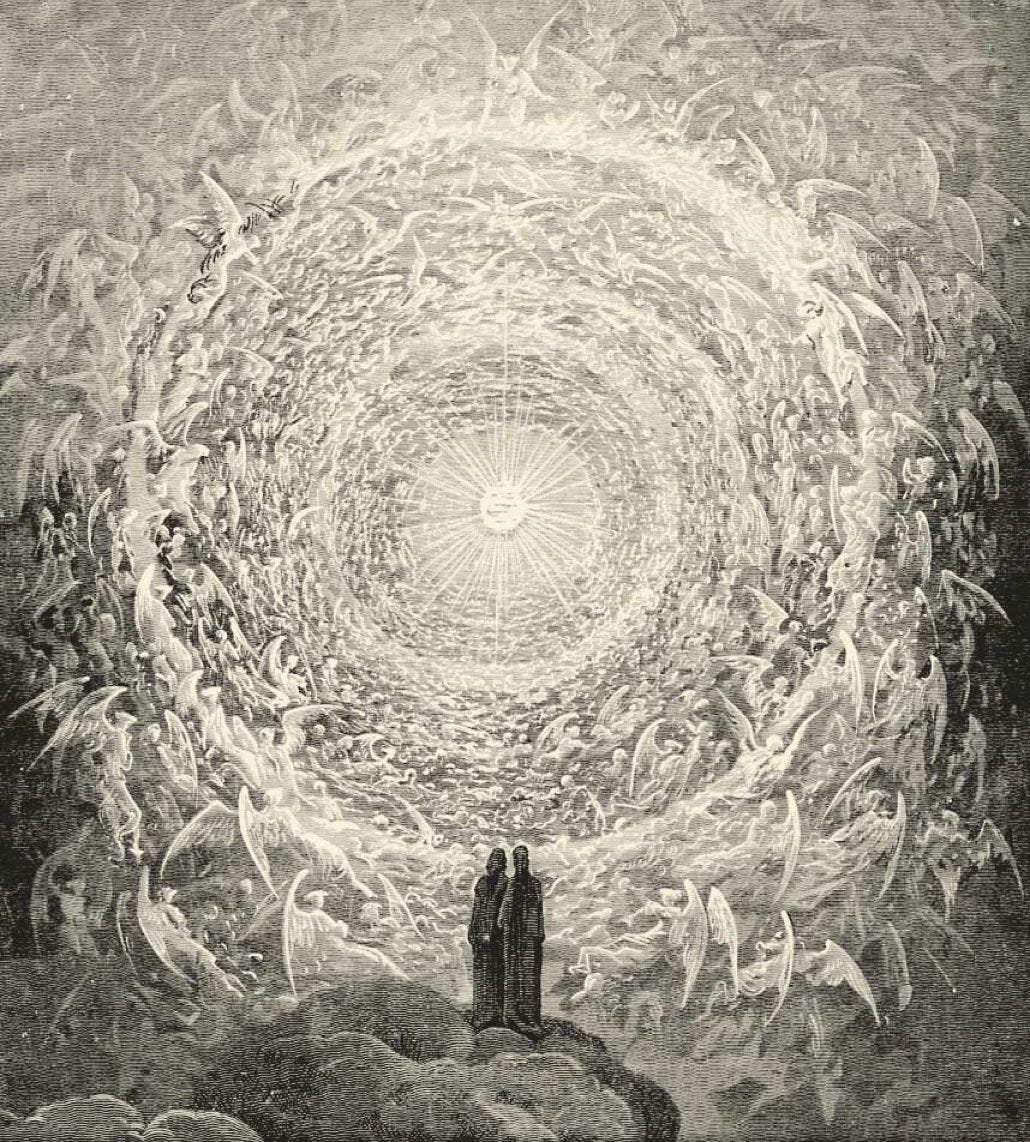

The thing the poem is, what it has become once placed on page and crafted, is a rough facsimile of the poem as it was felt by the poet. It has been brought down from the ether and explained in physical terms, i.e. words. The poem has undergone a necessary formalization. However, this formalization is almost entirely linguistic and is undertaken to capture some essence of the poem as it was felt.

In referring to this process as alchemical, let us not forget that in doing so a thing can be made worse or even better. I take the view that all poetry that undergoes this process of transformation is for the better, because it makes it understandable by more than just the poet who penned it — or who summoned it out of some Akashic Record.

It is ironic that a thing so overproduced, even a “simple” poem, can somehow be more real than real, more true than the raw thing itself. That is because poetry, if left in its purest and most base form, would be a series of letters and symbols written in a scrawling, painful hand across the page. It might not even be intelligible as words — think splotches of ink, odd sigils and symbols, doodles, parts of sentences, strange numbers, or single words repeated over and over.

When a raw emotion is revealed in all of its painful glory, it is often horrible and rarely beautiful to see — we say the words “ugly cry” for a reason. What is needed is a rational agent to tame the fear, to make the weirdness of the poet understood from the outside; oftentimes this “rational agent” is the poet in his more lucid moments. Think of it like watching a storm as opposed to being in the middle of it. The poem, then, is that thing which makes seeing the emotion possible.

If a poet did leave nothing by scratches and markings, it would be intelligible only to the poet themself; for every poet speaks their own poetic language. The thing you read is, really, nothing more than a translation from one language into another. The poet just does their best, using the literal words available and known to them, to make the poem make sense. To capture and distill feelings as best they can.

In doing all this, the poet can undertake a part in the greater re-enchantment of the world. The world for the vast majority of human history has been one where the natural and supernatural went together — one might not split them, because to do so would eliminate both. Enchantment in and with things, whatever they were and regardless of if they were made by human hands or the earth itself, was normal. Think of how forests were once sacred places (in every culture), yet now are seen as little more than standing reserves of lumber.

Re-enchantment is something that can be done in one of two ways: it can happen accidentally or with a great deal of concerted effort. Either course, however, lifts the veil. For what the veil is is nothing more than a bland scientism that, in its love of facts, ignores truths; it means discovering meaning in a world reduced to atoms. Lifting the veil is to make sense of our senses — the senses as we know them, and the senses as they could be.

This is not a screed against science, for science and scientism are different things; the first is curious about things as they are and can be (and has been) a boon for any number of reason, whereas the other is obsessed with reducing things to their constituent parts at the expense of the greater whole. Science, then, and enchantment can work together side-by-side, for what is a curiosity to know but to be enchanted by the thing at hand? If a thing enchants you, you seek earnestly to know it. This enchantment, then, is always just below the surface of much of what we do.

My first poetry collection — which is available as both an e-book and a paperback — originally carried the subtitle “A Grimoire of Poetry.” While that qualifier was dropped, its essence remains. It’s essence lingers because it must, because poetry has power because words have power. They are, in a manner of speaking, spells and where does a witch or wizard keep their spells? In a grimoire. Every book of poetry, rightly considered, could be seen as a grimoire of some kind.

Most poems, then, can be read in two ways. The first is how the author meant the poems to be read and understood. They are creations of one writer and reflect, in that way, whatever he happened to be feeling when he wrote them. The second way to read them is by looking at the poems as stars in the night sky — what strange shapes these points of light seem to make, how long have they looked down on us, what do they mean, and what meaning can I give them and take from them? It is to interpret the words you read as however you need to read them.

Finding your own meaning in poetry free from whatever the author may, or may not, have meant can be fun, thought-provoking, and even life-changing. Both searching for the author’s intent and doing away with the author entirely are both excellent ways to read a poem. And, as an aid to both methods, let me add that the poems can feel very different when read with the eyes then when spoken aloud with the voice. That kind of transformation, as simple as it sounds, works a kind of alchemy on the poetry itself; and that too is a kind of magic.

As one can see, so many things in life are already enchanted — if you let them be. The poet, any poet, should hope to act like a guidepost; we may not know the correct number of steps you must take, but we can help point you in the right direction. Sometimes we need exact mileage and sometimes all we have to go by is an arrow and the words “This Way.”

Reinvigorating ourselves is to reinvigorate the world at hand and, to find enchantment inside is to do the same outside. This idea that a sense of wonder and enchantment can help us combat the natural pull to a narrow, self-regarding, and utilitarian view of the world is to not only re-enchant, but to liberate.

In Latin, the word mirabilia means several different, yet related, things — wonders, marvels, miracles. It is time now for us to work our own miracle of re-enchantment, to create our own wonders and marvels. Let everyone be a poet, and let the world be reminded of its enchantment. Let us cease to see the lumber and let us fall back in love with the trees.