Frederick Douglass, like anyone worth their salt in nineteenth-century America, loved quoting scripture. Douglass, in his essay “The Union and How to Save It,” echoed a parable that appears three times in the New Testament. Compromises, he wrote, are “but as new wine to old bottles, new cloth to old garments.” His argument, penned in February 1861, was that the time for compromise had passed. He was to be proven correct.

Compromise, as novelist Shelby Foote said during an interview in Ken Burns’ The Civil War, was one of America’s great talents. “Our true genius is for compromise,” he said. More than thirty-years after the series’ debut, Foote would have found an unlikely ally in Donald Trump.

“The Civil War was so fascinating, so horrible,” Trump said. “So many mistakes were made. See, there was something that could've been negotiated, to be honest with you, I think you could have negotiated that.” Trump, like Foote, thought that maybe, just maybe, the Civil War could have been negotiated out of existence.

The problem is that Americans don’t actually compromise with one another. What they do, more often than not, is agree to kick the proverbial can down the road; they agree to let some other political actor from some subsequent generation figure it all out. The road to the Civil War was paved with compromises: The Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The onus of finding an actual solution was always left to the future.

A fetish for compromise isn’t usually connected to the Lost Cause, but a place could be made for it. The idea, baked into the daily bread of White Southerners for generations, was (and is) simply that the Civil War was never about slavery. The old chestnut for what caused the Civil War was usually states’ rights, or the threat (realistically non-existent in the age of the telegraph) of Big Government.

The trouble was that the moment the war began, the argument for states’ rights was thrown out the window. The southern states united and created a centralized national government, the leaders of which were, for the most part, wealthy, intelligent, and aristocratic slave-owners. The new confederacy created its own currency, quickly passed conscription laws, and made efforts to nationalize the railroad. One curious law, passed early in the war, ensured that rich planters (those who owned twenty slaves or more) were exempt from military service.

Even the novice historian can see that the howl of “states’ rights” was nothing more than a thinly veiled casus belli. A great irony of the Civil War was that the Southerners (at least the wealthy, aristocratic slave owners) claimed to fear and despise a large, centralized government while then going out of their way to create one. The tragedy became farce.

During a town hall in New Hampshire, Nikki Haley - former governor of South Carolina and now a 2024 presidential candidate - was asked what the cause of the Civil War was? “I think the cause of the Civil War was basically how [the] government was going to run,” said Haley. "I think it always comes down to the role of government, and what the rights of the people are.”.

The right answer to both attendee and pundit, of course, was slavery. Slavery caused the Civil War. That was the answer Haley was supposed to offer and expected to give. Her claim that the question was asked by a “Biden plant” rings hollow, even if it were true, in the face of what was obviously a softball question.

A week later, during a different town hall, she had a chance to answer correctly.

“If you grow up in South Carolina, literally in second and third grade, you learn about slavery,” she said. “It is a very talked-about thing. We have a big history in South Carolina, when it comes to, you know, slavery. When it comes to all the things that happened with the Civil War, all of that.”

The problem with Haley’s responses wasn’t that the Civil War was fought over slavery - it was. “Now, what disturbs, divides and threatens to bring on civil war, and to break up and ruin this country,” wrote Douglass in his February 1861 essay, “but slavery?” The problem is that Haley was both right and wrong both times.

The problem is that the Civil War wasn’t fought over slavery qua slavery, but over whether slavery would be the defining characteristic of America’s economic system. Morality, while a useful argument, ignores the fact that economics were the crux of the issue. And though there are very few things powerful enough to leverage control over entire economic systems, governments - particularly Big Governments - are one of them.

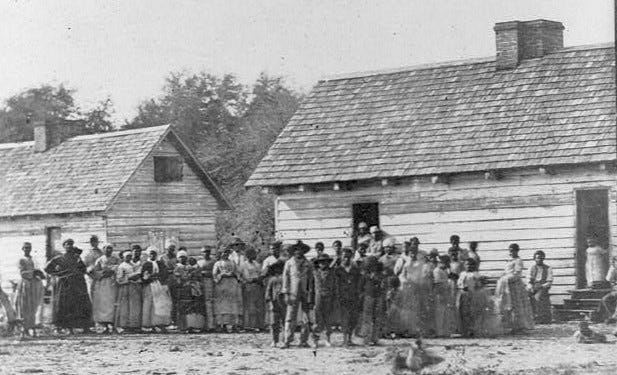

On the eve of the war, the South was wealthy. In 1860, the economic value of all slaves in the United States (mostly located in the South) exceeded the value of all of the nation's railroads, factories, and banks combined. That immense Southern wealth, however, was shackled to its slave economy.

The South understood just how wealthy slavery made them. “In [terms] of material wealth and resources, we are greatly in advance of them [the North],” said Alexander Stephens, the newly-elected Vice President of the Confederacy, during a speech to the Confederate congress in March 1861.

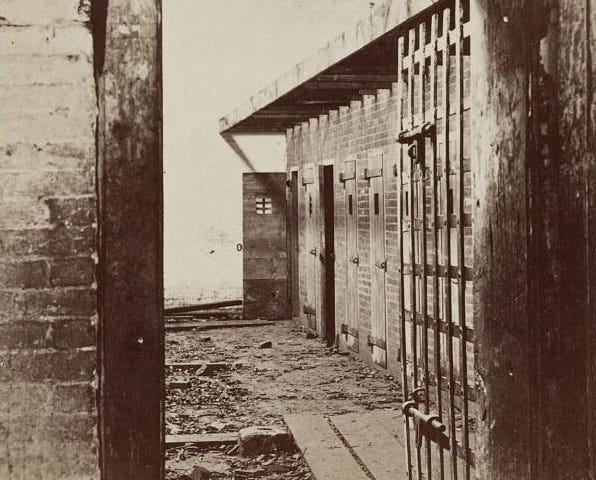

Stephens’ address that day would be known as the Cornerstone Speech, famous (and infamous) for its pronouncement that the Confederate government was founded upon “the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” In addition to being the Confederacy’s new vice president, Stephens owned almost three-dozen slaves.

Karl Marx, writing for Die Presse in October 1861, saw Stephens’ speech as a cover for a war by which the wealthy planter class hoped to preserve its political dominance over the entire country. “...now for the first time,” Marx wrote, “slavery was recognized as [an] institution for good in itself, and as the foundation of the whole state edifice.”

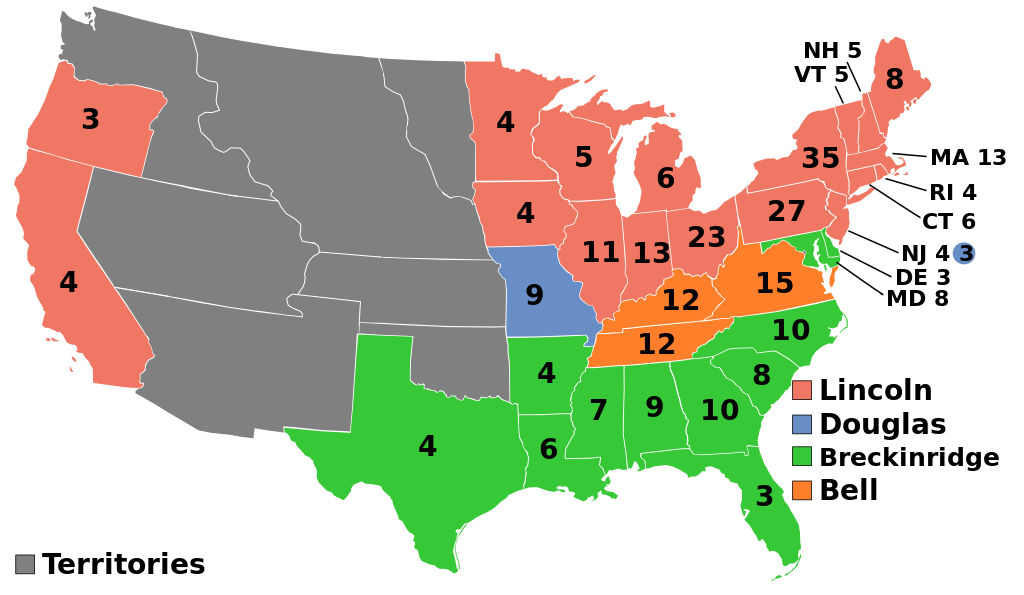

Marx was right, and not just about the South’s new government. While Stephens’ speech was about the new Confederate government, his words were equally applicable to the United States as a whole. What he said had been the de facto law of the land for much of the nation’s history. Until Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 election, almost every US president was either a slave owner or pro-slavery. Slave owners routinely dominated both Congress and the Supreme Court. Even Lincoln - the future Great Emancipator - was himself politically ambivalent towards slavery and had no personal wish to end it.

The problem for rich Southerners was not that Lincoln had no interest in touching slavery, but that he had been elected without their support. Lincoln failed to appear on the ballots of ten different southern states, but was still elected to the presidency. This meant that, as far as Southerners were concerned, Lincoln was beyond their grasp and outside of their control. Who knew what he might do, what changes he might make? The South couldn’t have that. Before 1860 was over the first state of the future Confederacy, South Carolina, would secede.

Nikki Haley is a child of South Carolina just as much as she is a child of two immigrant parents from Punjab. Like she said: “If you grow up in South Carolina…you learn about slavery.” Of course you do. When Haley said the Civil War was about the role of government, she was right. When she said the war was about slavery, she was still right.

The Civil War was about slavery, the economic system that slavery was an essential part of, and whether that system - and thus slavery - would be protected by the government. That protection was secure so long as slave owners or pro-slavery advocates held the presidency, Congress, and the Supreme Court. The moment they lost control, the South seceded.

“Government doesn't need to tell you how to live your life,” Haley said. Tell that to Alexander Stephens and his thirty-four slaves.